Top 10 Events in Black American History

Black American history is a 400-year saga of resilience, struggle, and triumph. From the first arrival of enslaved Africans in 1619 to the election of the first Black U.S. president in 2008, certain key events stand out as turning points. These milestones shattered barriers, ignited civil rights movements, and pushed the United States closer to its professed ideals of freedom and equality. This chronological overview of the top ten events in Black American history, aimed at students and educators, highlights not only the well-known victories but also clarifies common myths and sheds light on under-told aspects of each event. Understanding these events is crucial to grasping the timeline of Black history and the ongoing quest for civil rights and social justice.

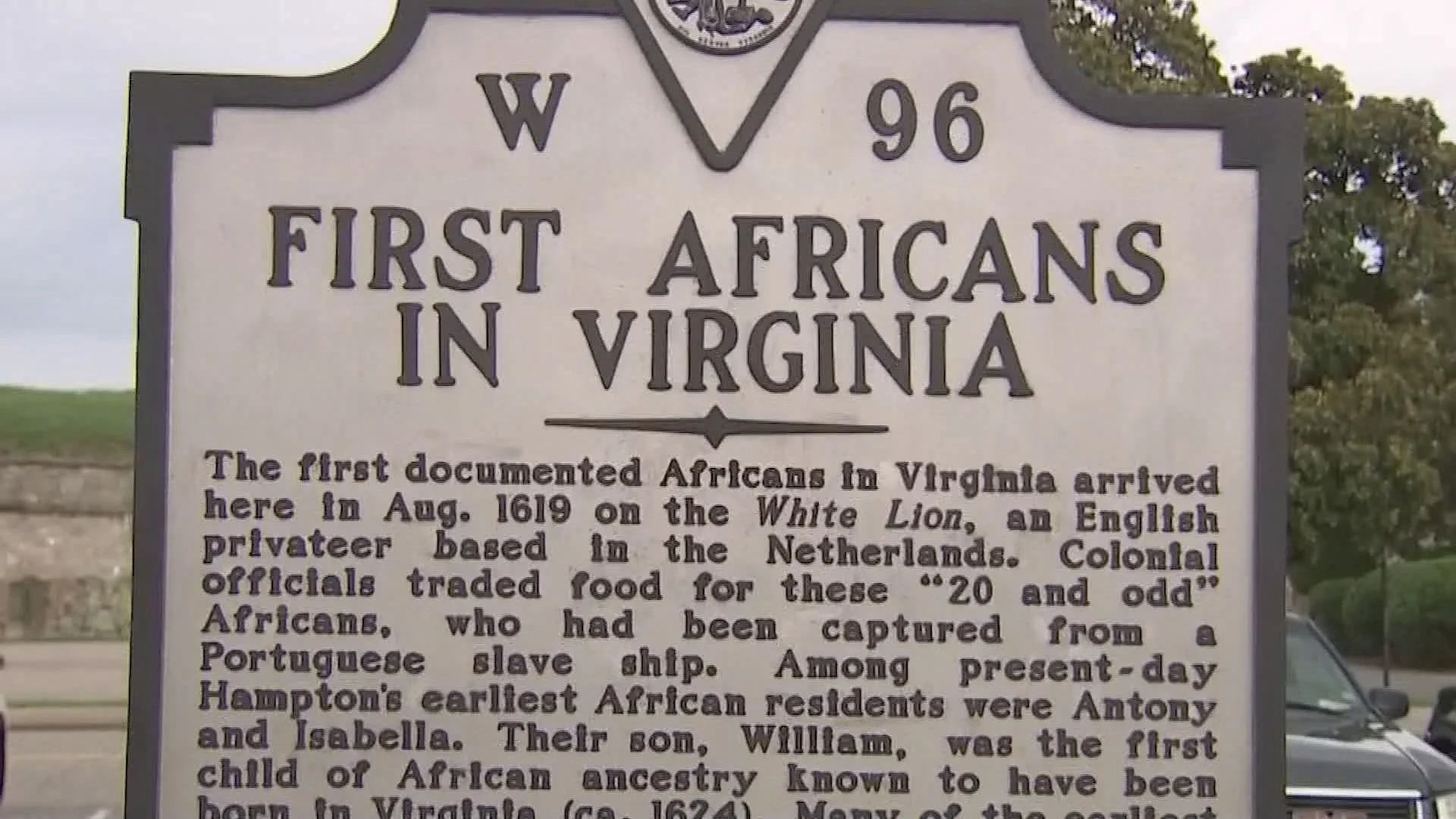

1619: First Enslaved Africans Arrive in Virginia

In late August 1619, about 20 captive Africans from the kingdom of Ndongo (present-day Angola) were brought to the English colony of Virginia at Point Comfort (now Fort Monroe) and sold to colonists. This moment is often cited as the beginning of African-American slavery. Early records described these Africans as “indentured servants,” but in reality, they were forced into perpetual servitude, meeting the definition of enslaved people. Some did eventually obtain a form of freedom, yet the myth that they were simply voluntary indentured servants obscures the coercion involved. The 1619 arrival ignited a system of race-based chattel slavery that would endure in North America for 246 brutal years. Sometimes called America’s “original sin,” slavery became central to the colonial economy and left a legacy that the nation still grapples with today. This first event in Black American history set the stage for centuries of struggle over the meaning of freedom and human rights in the United States.

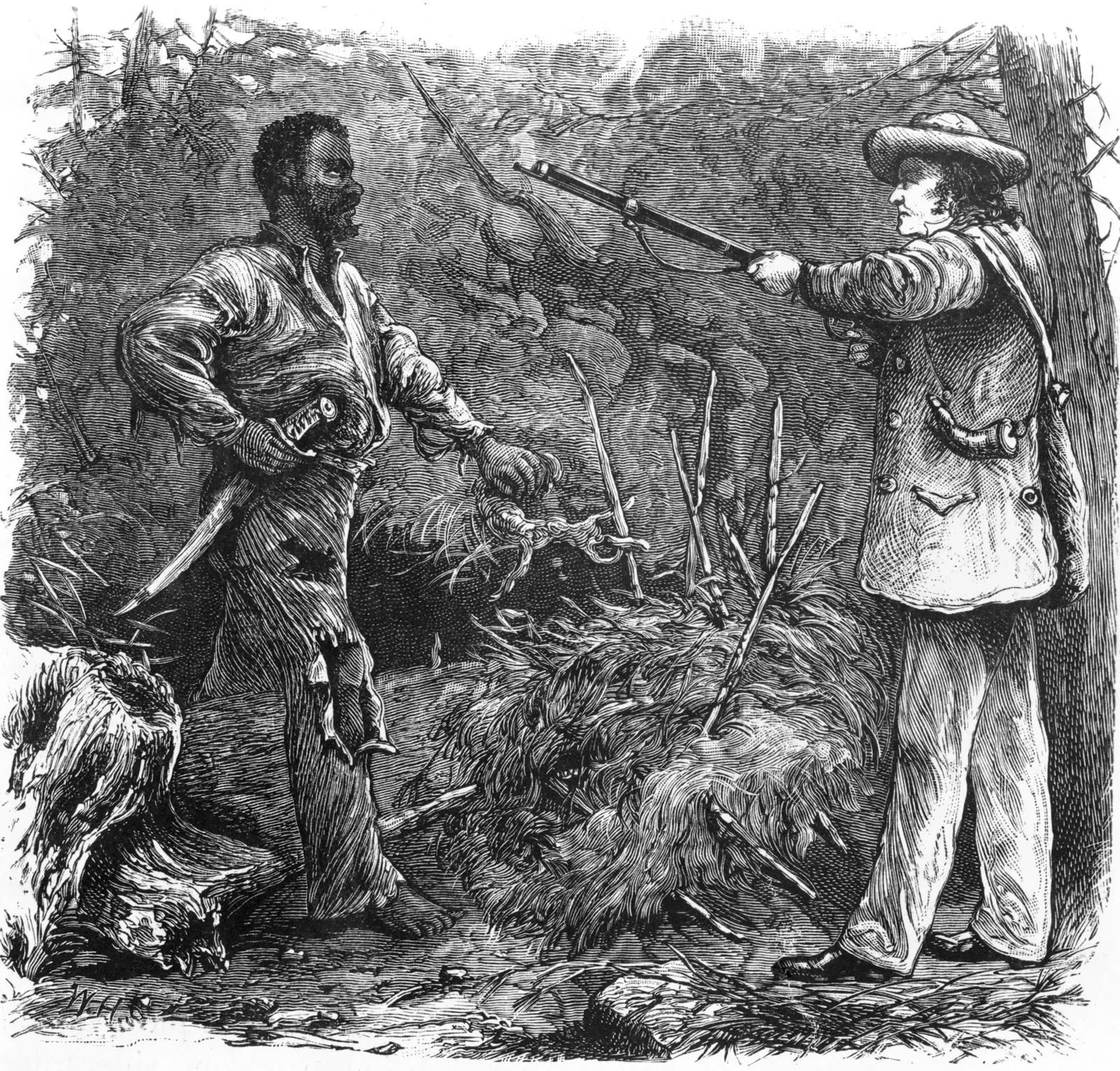

1831: Nat Turner’s Rebellion

The Discovery of Nat Turner,” engraving from Popular History of the United States, published by William Cullen Bryant and Sidney Howard, 1881–88

Nat Turner’s Rebellion in August 1831 was one of the most significant and fearsome revolts by enslaved people in American history. Turner, an enslaved Black preacher in Southampton County, Virginia, felt divinely called to lead an uprising against the slaveholding regime. On August 21, 1831, he and a small band of fellow enslaved people launched a violent revolt, moving from plantation to plantation. In the span of two days, Turner’s rebels killed around 55 to 60 white people in the area, striking terror into the slaveholding South. The rebellion was eventually crushed by local militias.

Turner went into hiding for weeks but was caught and executed, along with some 16 of his followers. In retaliation, white mobs killed as many as 100–200 African Americans, many of them not involved in the revolt, in a bloody wave of retribution. In the rebellion’s aftermath, Southern states passed harsh new laws prohibiting the education, movement, and assembly of enslaved people, fearing another uprising. Nat Turner’s bold action shattered the prevailing myth that enslaved people were content or too docile to resist their condition. It also polarized the nation: abolitionists saw the rebellion as evidence of slavery’s injustices, while pro-slavery forces became even more entrenched – bringing the country one step closer to the Civil War.

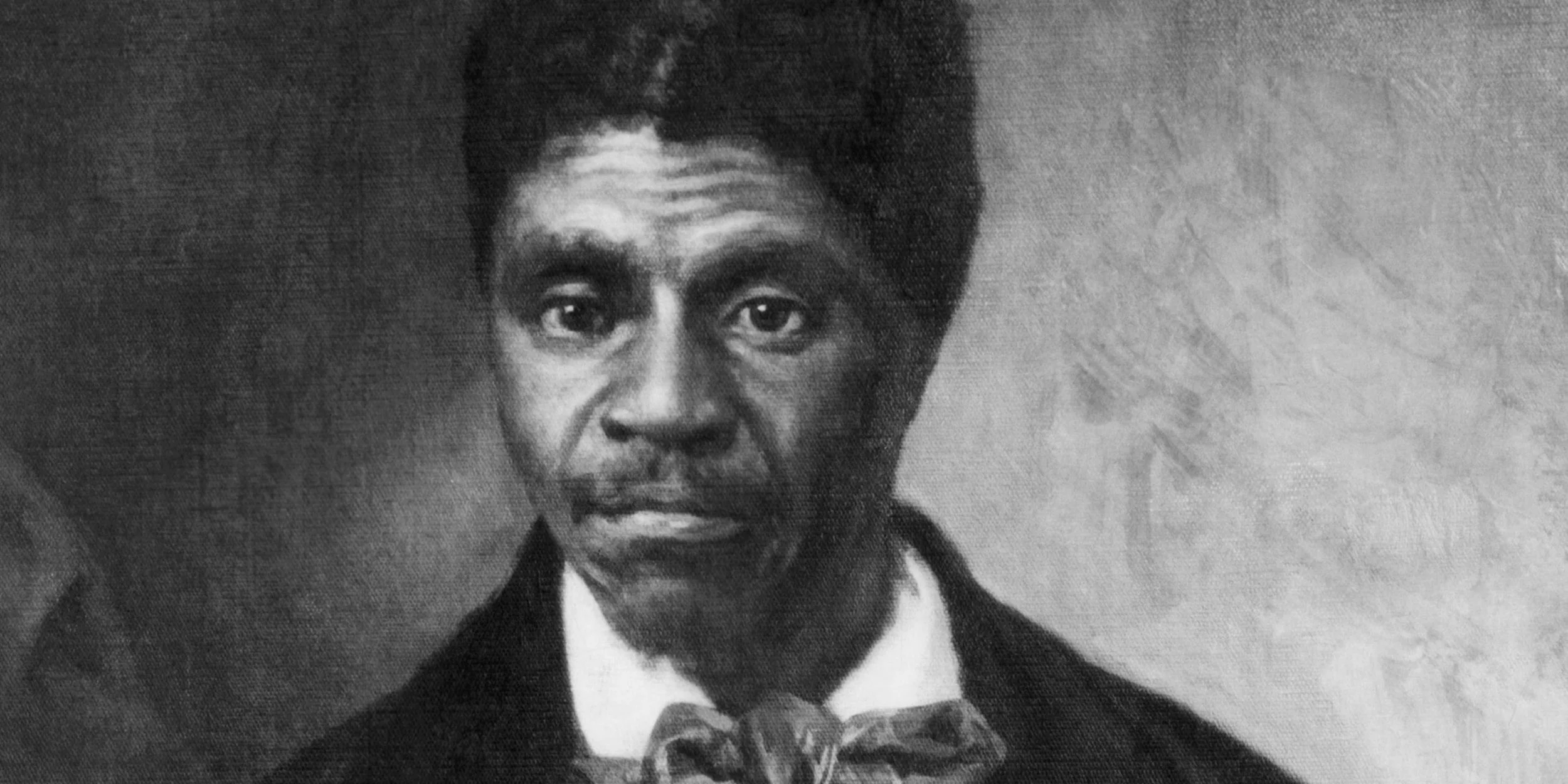

1857: The Dred Scott Decision

n March 1857, the United States Supreme Court delivered one of its most infamous rulings in Dred Scott v. Sandford, a case that would deepen the national divide over slavery. The Court, led by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, declared that African Americans – whether enslaved or free – were not and could not be citizens of the United States, and thus had no right to sue in federal court. In Taney’s sweeping pro-slavery opinion, he wrote that Black people “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect”. This decision also struck down the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by asserting that Congress had no authority to ban slavery in the federal territories, opening all western territories to the potential spread of slavery. The Dred Scott decision was a devastating blow to Black Americans and abolitionists, effectively legalizing slavery in all corners of the country and nullifying decades of political compromise.

Far from settling the issue, the ruling inflamed Northern public opinion and is widely regarded as a direct catalyst for the Civil War. It took the Civil War and constitutional amendments to undo Dred Scott: the 14th Amendment (1868) later affirmed birthright citizenship and equal protection, nullifying the Court’s denial of Black citizenship. Myth busting: It’s often believed that the Supreme Court always stood as an impartial arbiter of justice; Dred Scott illustrates how the Court itself enshrined racism, requiring immense struggle and bloodshed to overturn. The case’s legacy underscores why it is frequently cited as the worst Supreme Court decision in U.S. history, a stark reminder of how law was used to uphold slavery.

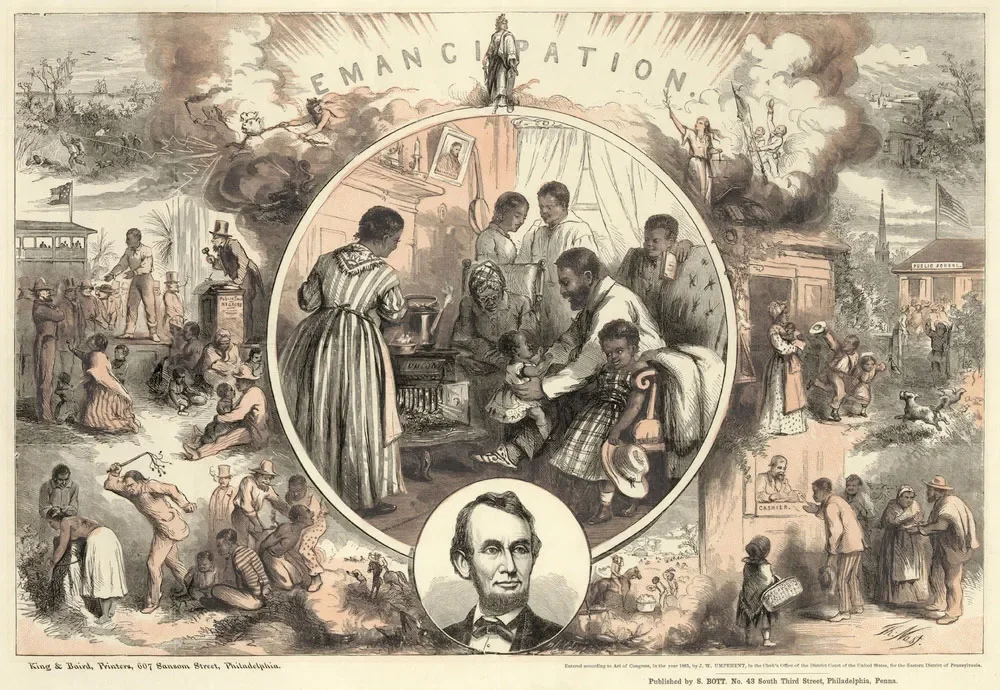

1863: The Emancipation Proclamation

The Civil War (1861–1865) began as a conflict to preserve the Union, but by 1863 it had become unequivocally a war to end slavery. President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, was a turning point in that transformation. The proclamation declared that “all persons held as slaves” in the rebelling Confederate states “are, and henceforward shall be free”. This executive order applied only to the states in rebellion (the Confederacy) and explicitly excluded the Border States (like Kentucky, Maryland, etc.) and any Confederate areas already under Union control. This limitation gave rise to the misconception that the Emancipation Proclamation “freed no one,” since it didn’t immediately free slaves in areas where Lincoln’s government had authority.

In truth, wherever Union armies advanced into the South after January 1, 1863, they were literally agents of liberation, as Union troops arrived, enslaved people were set free. Moreover, the proclamation carried immense moral and strategic weight: it made abolition a central Union war aim, dissuaded foreign powers (like Britain or France) from siding with the Confederacy, and authorized the recruitment of Black men into the Union Army and Navy. By war’s end, nearly 200,000 African Americans had fought for the Union cause, their service crucial to Union victory and to their own liberation. While the Emancipation Proclamation did not legally end all slavery (that required the 13th Amendment in 1865), it is rightly celebrated as a “mighty blow” against the institution of slavery. It refuted the myth that Lincoln “freed not a single slave” – tens of thousands were in fact freed as federal troops moved South. Equally important, the proclamation changed the very character of the war and “added moral force to the Union cause,” ensuring that a Union victory would mean true emancipation for four million enslaved African Americans.

1865: Juneteenth and the End of Slavery

By 1865, the Confederacy was in ruins, and slavery’s days were numbered. Two pivotal moments that year finally brought American slavery to an end. The first came on June 19, 1865, in Galveston, Texas – a date now commemorated as Juneteenth. On that day, Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived with troops in Galveston and publicly read General Order No. 3, announcing that, in accordance with Lincoln’s proclamation, “all enslaved people are now free” in Texas. Texas, the remotest Confederate state, had not seen much Union occupation, so many enslaved Texans were only learning of their freedom upon Granger’s arrival, a full two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth thus marks the moment the last enslaved African Americans were notified of their freedom, and it has been celebrated since 1866 as Emancipation Day or Freedom Day. (It became recognized as a U.S. federal holiday in 2021, underscoring its importance in the American story.)

The second moment came in December 1865, when the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, abolishing slavery (and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime) throughout the United States. The 13th Amendment permanently enshrined what Juneteenth symbolized – the total legal end of chattel slavery on American soil. Together, these events dispel a common misconception that the Emancipation Proclamation alone ended slavery. In reality, freedom came in waves: first declarations (1863), then enforcement (1865 via Juneteenth), and finally a constitutional guarantee (Dec 1865). The end of slavery was greeted with jubilation among the freedpeople, but also foreshadowed new struggles. The language of Granger’s Order No. 3 urged freedpeople to remain with their former masters as paid laborers and warned against “idleness”, a sign that, although slavery was abolished, true equality remained elusive. Nevertheless, Juneteenth and the 13th Amendment together represent a monumental milestone: the destruction of slavery in the United States, achieved through the sacrifice of the Civil War and the courage of millions of enslaved people who had long resisted bondage.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education Ends School Segregation

The modern Civil Rights Movement gained huge momentum with the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka on May 17, 1954. This landmark case struck at the core of Jim Crow segregation. The Court overturned the old “separate but equal” doctrine (from Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896) by ruling that racial segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In eloquent language, Chief Justice Earl Warren declared that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The Brown ruling was actually a consolidation of cases from several states, brought by Black families (with support from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund) who challenged the denial of equal educational opportunities. By deeming segregation unconstitutional, Brown dealt a deathblow to the legal framework of segregation, at least on paper.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education Ends School Segregation

The modern Civil Rights Movement gained huge momentum with the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka on May 17, 1954. This landmark case struck at the core of Jim Crow segregation. The Court overturned the old “separate but equal” doctrine (from Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896) by ruling that racial segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In eloquent language, Chief Justice Earl Warren declared that “in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The Brown ruling was actually a consolidation of cases from several states, brought by Black families (with support from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund) who challenged the denial of equal educational opportunities. By deeming segregation unconstitutional, Brown dealt a deathblow to the legal framework of segregation, at least on paper.

This decision is often remembered for its uplifting legal promise, but it’s important to note the aftermath: Brown faced massive resistance from white segregationists across the South. Many Southern states and school districts employed every tactic imaginable, from shutting down public schools, to creating private “segregation academies,” to legislative delays, in order to avoid integration. As a result, actual school desegregation proceeded slowly. By 1960, only a tiny fraction of Black children in the Deep South attended integrated schools. It would take another Supreme Court order (Brown II, 1955, calling for desegregation “with all deliberate speed”) and vigorous enforcement in the 1960s and beyond to make school integration a reality. Brown v. Board, however, remains a cornerstone of civil rights law. It inspired Black Americans and civil rights activists to push for further change, proving that the highest court in the land would side with justice, even if society was not yet ready. The case also dispelled the myth that “separate” could ever truly be “equal” – a myth that had long been used to justify segregation. Brown was the beginning of the end for de jure segregation in America, and it set the stage for the larger Civil Rights Movement victories to come.

1955–1956: The Montgomery Bus Boycott

One of the first great triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement was the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a year-long mass protest in Montgomery, Alabama, that broke the back of segregated public transportation. The boycott began on December 5, 1955, sparked by the courageous act of Rosa Parks four days earlier. Parks, a 42-year-old Black seamstress and civil rights activist, was arrested on December 1, 1955 for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery city bus. Her quiet act of defiance – often misunderstood as mere personal tiredness, when in fact Parks famously said “the only tired I was, was tired of giving in,” reflecting her longstanding activism – galvanized Montgomery’s Black community. Black women from the Women’s Political Council had been planning a bus protest for some time, and in the wake of Parks’ arrest, Black leaders (including a young Baptist minister named Martin Luther King Jr.) organized a boycott of the city buses. About 90% of Montgomery’s Black residents participated, finding alternative transportation or walking miles to work for 381 days.

This incredible display of unity and nonviolent protest put economic and moral pressure on the city. The protesters persisted despite arrests, harassment, and even the bombing of Dr. King’s house. The boycott’s success was sealed when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling in Browder v. Gayle (1956) that bus segregation was unconstitutional, leading Montgomery to finally integrate its bus system. The Montgomery Bus Boycott demonstrated the power of sustained, grassroots activism and introduced Dr. King as a national civil rights leader. It also debunked a common myth that the civil rights victories were won overnight by charismatic leaders alone; in truth, the boycott showed the world what an organized Black community – including many unsung women activists – could achieve with strategic planning and collective action. The Montgomery boycott became a blueprint for the larger movement, proving that nonviolent mass protest could effectively challenge and dismantle segregation.

1963: The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

MLK JR. giving a speech

view of some of the 250,000 participants during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. This historic gathering at the Lincoln Memorial became one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in U.S. history. On that day, over a quarter of a million people – Black and white, from all across the nation, converged on Washington, D.C., in a peaceful rally to demand civil rights, voting rights, and economic opportunity. Officially called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the event was the result of a massive collaborative effort by civil rights leaders (the “Big Six,” including A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, James Farmer, and John Lewis) and many labor and religious organizations. Demonstrators gathered at the Lincoln Memorial, carrying signs calling for desegregation, fair housing, equal employment, and the passage of a strong civil rights law. The march is best remembered for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to the sea of people sprawled down the National Mall. In that iconic oration, King envisioned a future where the nation would fulfill its promise of equality, where people would be judged “not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

The March on Washington is widely credited with building public support for civil rights legislation. Less than a year later, President John F. Kennedy’s proposed civil rights bill (which marchers were advocating for) was passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Myth vs. reality: Many people recall the uplifting spirit of the march and King’s words, but might not realize that the full name was “for Jobs and Freedom”, highlighting economic justice alongside civil rights. In fact, the march was as much about employment discrimination and poverty as about ending segregation. Another underappreciated aspect is the role of organizers like Bayard Rustin (the march’s chief coordinator, who was an openly gay Black activist often kept in the background) and the participation of women, although no woman gave a major speech, figures like Dorothy Height and Mahalia Jackson were influential in the event. The March on Washington showcased Black Americans’ ability to mobilize en masse and appeal to the nation’s conscience. Televised live to millions, it marked a high point of hope and solidarity in the Civil Rights Movement and pushed the country closer to the landmark reforms of the 1960s.

1964: The Civil Rights Act of 1964

By the mid-1960s, the civil rights movement’s persistence led to one of the most consequential pieces of legislation in American history: the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Signed into law on July 2, 1964, by President Lyndon B. Johnson (who had taken up the cause after President Kennedy’s assassination), the Act outlawed racial discrimination and segregation in many facets of public life. It banned segregation in public accommodations (such as hotels, restaurants, theaters, parks, and swimming pools) and prohibited employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin by most large employers and unions. The law also encouraged school desegregation and provided new protections for voting rights (although a stronger Voting Rights Act would follow in 1965). Achieving this legislation was extraordinarily difficult: it faced a determined filibuster by segregationist senators, a filibuster that lasted 60 working days, the longest debate in Senate history at that time. In a dramatic showdown, the Senate was able to invoke cloture (end debate) for the first time ever on a civil rights issue, with key support from both Northern Democrats and Republicans.

The Act passed the Senate and House in June 1964, and when Johnson signed it into law (with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders present at the White House), he reportedly said, “We have delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come,” acknowledging the political cost of supporting civil rights. Myth-busting note: Some assume the Civil Rights Act instantly solved racism, but while it legally ended de jure segregation, it did not end racial disparities or prejudice. It did, however, dismantle the legal foundation of Jim Crow and gave the federal government enforcement powers to actively intervene when civil rights were violated. The Act also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to address workplace discrimination. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a crowning achievement of decades of activism – from NAACP legal battles to grassroots protests – and it stands as a milestone of progress. Alongside the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (which targeted racist voter suppression), the Civil Rights Act transformed American law by affirming that segregation and discrimination have no place in a society of equal citizens. Its legacy is evident every time one walks into an integrated school, casts a vote, or starts a new job without legally sanctioned bias.

2008: The Election of Barack Obama

On November 4, 2008, Barack Hussein Obama II was elected the 44th President of the United States – the first African American to hold the nation’s highest office. This moment was hailed around the world as a transformative milestone in Black American history and in the overall American narrative. Obama’s decisive victory (winning 365 electoral votes and just over 52% of the popular vote) over Senator John McCain was culturally and historically significant on multiple levels. It occurred 145 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and just 40 years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., a juxtaposition that many commentators noted in awe. The symbolism was impossible to miss: a country that once enslaved Black people and enforced Jim Crow laws had, within two generations of the civil rights movement, elected a Black man as President. Obama carried former strongholds of the Old South like Virginia, where not long ago segregation reigned and interracial marriage was illegal – a fact often cited as astonishing evidence of social progress. His campaign and election also led to unprecedented Black voter enthusiasm and turnout; for the first time in U.S. history, the percentage of Black Americans who voted in a presidential election surpassed the percentage of whites who voted.

The night of Obama’s win, civil rights hero Jesse Jackson was seen tearfully observing the celebration in Chicago’s Grant Park – later saying that Obama’s achievement showed “there’s nothing else we can’t be” as Black Americans. However, Obama’s presidency also invites reflection beyond the celebratory narrative. While many people spoke of a “post-racial” America after 2008, that optimism was tempered by reality. Obama himself noted that his election was not a magic solution to racial inequality, and indeed, racial tensions and disparities persisted (and in some cases, became more visible) during his two terms. The myth some held – that Obama’s presidency meant the U.S. had fully overcome its racist past- was quickly challenged by events such as the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, which emerged in response to continued racial injustices in policing during Obama’s tenure. Nonetheless, the educational and inspirational value of Obama’s rise is undeniable: it inspired a new generation of young Black people to imagine broader horizons and careers in public service, and it shifted global perceptions of American democracy. Obama’s election stands as the capstone of this top ten list, illustrating both how far the nation has come and how the journey for equality continues. It underscored the idea that Black history is American history, interwoven into the nation’s highest echelons of leadership

Conclusion

The top ten events highlighted above form a vivid timeline of Black American history – from the 17th-century genesis of slavery through 19th-century emancipation, and from the mid-20th century civil rights triumphs to barrier-breaking achievements in the 21st century. Each milestone was hard-won, born of the courage and persistence of countless individuals. It’s important to remember that for every famous figure like Martin Luther King Jr. or Rosa Parks, there were thousands of unsung activists, foot soldiers, and community members whose efforts made these victories possible. These events carry immense educational value: they help students and the public understand how deeply Black Americans have shaped U.S. history and how the quest for justice has been integral to the American experience. They also dispel myths, reminding us, for instance, that freedom didn’t simply “happen” with one document, or that civil rights were not simply granted by enlightened leaders but rather demanded by people working collectively.

Studying these milestones invites reflection on the progress achieved and the challenges that remain. The legacy of these events is all around us, in the diversity of our schools and workplaces, in the legal protections we often take for granted, and in the ongoing movements for social change. Black history is not a separate thread but the very fabric of American history, and these milestones are cornerstones of the broader narrative of freedom and equality. By learning about them, we honor the struggles and contributions of Black Americans, and we equip ourselves to continue the work of building a more just and inclusive society.

Sources:

Historic Jamestowne, “The First Africans,”Encyclopedia Virginia (2019)

Britannica, “Nat Turner’s Rebellion,”Encyclopædia Britannica (2026)

PBS, “Dred Scott case: the Supreme Court decision,”Africans in America (WGBH/PBS)

U.S. National Archives, “Emancipation Proclamation (1863),”Milestone Documents

National Archives News, “Juneteenth General Order No. 3,” by Michael Davis (2020)

Stanford King Institute, “Montgomery Bus Boycott,”King Encyclopedia

Equal Justice Initiative, “Brown v. Board of Education – On This Day” (EJI Calendar)

NAACP, “The 1963 March on Washington – History Explained,”NAACP.org

U.S. Senate Historical Office, “The Civil Rights Act of 1964 – Landmark Legislation,”Senate.gov

TIME Magazine, “What Obama’s Election Means to Black America,” by Kevin Merida (Nov. 2008)