George Washington Carver: More Than “The Peanut Man”

Watch Your Kid Professors, where kids teach history, culture, and the stories too often left out.

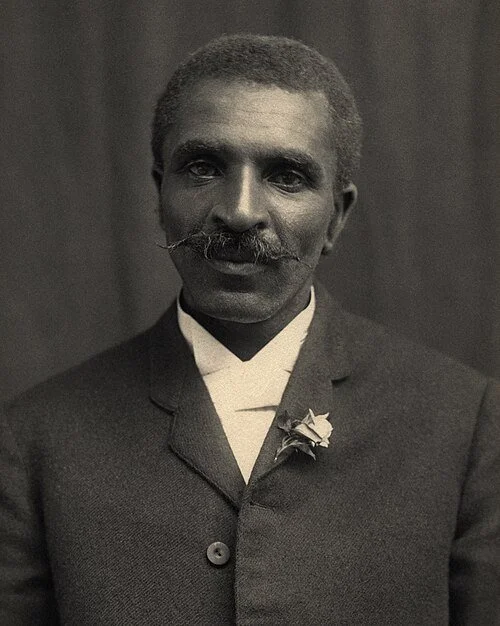

George Washington Carver (circa 1910), in a photograph from the Tuskegee Institute archives. He rose from enslavement to become a celebrated scientist and educator. Born enslaved during the Civil War, George Washington Carver defied the odds.He became one of America’s most famous agricultural scientists. He’s best known for his work with peanuts. He’s often mistakenly credited with inventing peanut butter, but Carver’s life story goes far beyond one crop or invention. In this post, we’ll explore George Washington Carver's facts.

We’ll separate myths from truth. We’ll highlight lesser-known aspects of his legacy.

George Washington Carver. The image has been restored, with dust spots removed1902.

Early Life and Education: From Slavery to Science Pioneer

Born into Slavery:

Carver was likely born in 1864. This was on the Missouri farm of Moses Carver, who enslaved his mother, Mary.

As an infant, George and his mother were kidnapped by slave raiders. Moses Carver managed to recover baby George, but his mother was never found.

After slavery was abolished in 1865, Moses and his wife, Susan, raised George. They even taught him to read, nurturing his early fascination with plants.

Neighbors dubbed him the “plant doctor” when he was a child. He had a knack for nursing sick houseplants back to health.

This early passion for nature set Carver on his life’s path.

Striving for Education:

Local schools refused Black children. So Carver left home around age 12 to pursue an education.

He moved through towns in Missouri and Kansas during his teens. This overlapped with the westward Exoduster migration of formerly enslaved people.

He attended school when he could. He worked odd jobs to support himself.

After finishing high school in Kansas, Carver was accepted to college in 1885. But administrators turned him away once they discovered he was Black.

Undeterred, he homesteaded a farm. He conducted his own botanical studies.

Finally, he gained admission to Simpson College in Iowa in 1890.

Artist Turned Botanist:

At Simpson College, Carver studied art and music. He was an accomplished painter of floral scenes.

He even exhibited artwork at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. His art teacher saw his talent for observing nature.

She encouraged him to pursue science. Carver transferred to Iowa State Agricultural College to study botany.

He became the first Black student to enroll there. He earned his Bachelor’s degree in 1894.

He got his Master’s in agriculture in 1896. He was one of the first African Americans to earn an advanced degree in agricultural science.

At Iowa State, Carver researched plant fungal diseases. He discovered two new species of fungi.

His professors were so impressed, they hired him. He became the school’s first Black faculty member.

Tuskegee Innovations: Crop Rotation and "The Peanut Man"

In 1896, Booker T. Washington invited Carver to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.He asked him to head the agriculture department.

Carver accepted. This began his 47-year career at Tuskegee.

There, he became a pioneering teacher and researcher. He found Southern farmers trapped in poverty.

The one-crop economy of cotton had depleted the soil. Carver introduced crop rotation.

He urged farmers to alternate cotton with soil-enriching crops. These included peanuts, soybeans, cowpeas, and sweet potatoes.

This revitalized the land. It gave farming families new sources of food and income.

When boll weevils devastated cotton crops in the early 1900s, Carver’s ideas proved lifesaving.

Carver faced a new challenge. Farmers had huge surpluses of peanuts and sweet potatoes.

He turned his laboratory toward finding novel uses for these crops. He developed, compiled, and publicized over 300 uses for peanuts.

He created more than 100 recipes for sweet potatoes. Peanut products included flour, plant-based milk, dyes, plastics, cosmetics, soap, insecticides, and even gasoline.

Sweet potato innovations included glue for postage stamps, synthetic rubber, vinegar, and ink.Carver shared these ideas in practical bulletins for farmers.

In 1916, he published "How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption."It included recipes for peanut breads, soups, and even peanut "coffee."

The Peanut Man in Washington:

In 1921, Carver’s peanut research made him nationally famous. He testified before the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee.

Peanut farmers sought tariff protection. At first, congressmen were skeptical of a Black scientist.

But Carver captivated them. He demonstrated dozens of peanut products—from flours and cheeses to colored dyes.

He explained the crop’s economic importance. The committee gave him unlimited time to speak.

Newspapers nationwide reported on the "Peanut Man."Carver and peanuts became linked in the public mind.

Years later, he humbly noted: "No, [it’s not my best], but it has been featured more than my other work."

Bringing Education to the People:

Carver’s most impactful work was educating poor Black sharecroppers. They had little access to schooling.

To reach remote farmers, he pioneered a "movable school."In 1906, he designed the Jesup Agricultural Wagon.

This horse-drawn mobile laboratory carried seeds, plants, tools, and exhibits. Carver traveled to rural communities.

He taught farmers on their own soil. They learned to improve crops, preserve food, and sustain their land.

New York philanthropist Morris Jesup funded the program. It was wildly successful.

It became an important model for later USDA extension programs.

Carver’s Jesup Wagon brought farming education directly to rural farmers. It demonstrated planting techniques, soil improvement, and new crops. The concept was ahead of its time.

Myth vs. Fact: Did Carver Invent Peanut Butter?

One common myth says George Washington Carver invented peanut butter. This is false.

Peanut butter existed long before Carver’s time. Indigenous Aztec and Maya peoples made peanut pastes centuries ago.

In the U.S., Dr. John Harvey Kellogg patented a peanut butter-like product in 1895. It was a protein substitute for people who couldn’t chew solid food.

By Carver’s research era, peanut butter was already known. It appeared at the 1904 World’s Fair.

Carver never claimed to invent it. His 1916 peanut bulletin even included peanut butter recipes.

While he didn’t invent peanut butter, Carver helped popularize peanuts. His promotion created a peanut farming boom.

This made peanut butter an American staple. Without Carver, peanuts might not be the major commodity they became.

Beyond Peanuts: Lesser-Known Sides of Carver’s Work

Carver’s achievements went far beyond peanuts and sweet potatoes. Here are fascinating, lesser-known facts:

Accomplished Artist: He was a skilled painter and pianist. His floral paintings were exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. This artistic eye steered him toward botany.

Plant Disease Researcher: Carver was a botanist and mycologist. At Iowa State, he discovered new species of fungi. He later led USDA efforts to track and prevent crop diseases.

Consulted by Leaders: U.S. presidents admired his work. Theodore Roosevelt engaged him on agricultural issues. Franklin D. Roosevelt supported conservation tied to Carver’s ideas.

Experimental Healer: In the 1930s, Carver tried peanut oil therapy for polio victims. Some reported improvement from his massages. Later studies showed peanut oil itself wasn’t the cure.

Principles Over Profit: Carver reportedly turned down a lucrative Edison job offer. He stayed at Tuskegee to help poor farmers. He patented only three of his hundreds of inventions.

A Man of Service: Carver’s Personal Life and Philosophy

Carver’s personal qualities matched his scientific achievements. He was deeply spiritual and humble.

His inspiration came from God and nature.

He never married and lived modestly.

He poured energy into research and mentoring students.

Former students called him kind, empathetic, and sometimes eccentric.

He was always willing to help others learn.

Carver valued service over fortune.

He wore shabby suits and spent little on himself.

He invested in his lab and students’ welfare.

He gave money to needy students and projects.

In 1917, he explained his motivation simply:

"When I leave this world, I want to feel that my life has been of some service to my fellow man."

Carver was a teacher at heart. He stayed at Tuskegee until his death.

He mentored generations of Black scientists and farmers.

His office door was open to anyone seeking advice.

He taught chemistry, agriculture, character, and curiosity.

“Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom”

Legacy and Honors: Remembering a Black Science Icon

George Washington Carver died January 5, 1943. He was around 78 after falling down stairs at Tuskegee.

His impact was immediately recognized. President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 for a monument.

The George Washington Carver National Monument opened in Diamond Grove, Missouri. It was the first U.S. national monument dedicated to an African American.

It was also the first to honor someone other than a president. This reflected Carver’s status as one of America’s most accomplished citizens.

Carver’s legacy endures in many forms. He received the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in 1923.

He was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Dozens of schools, libraries, and scholarships bear his name.

In his will, he created the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee. It endows agricultural research for future Black scientists.

Each February during Black History Month, students learn about Carver. He broke barriers in education and science.

Carver showed scientific research could help the vulnerable. He taught sustainable agriculture before "environmentalism" was a buzzword.

Born into slavery, he became a nationally respected scholar and advisor. His perseverance inspired millions.

He disproved racist ideas about Black scientific ability. He paved the way for future Black scientists and inventors.

Why Carver Still Matters

George Washington Carver’s journey inspires today. From enslaved child to honored scientist, he showed what’s possible.

He blended expertise with compassion. True success comes from serving others, he believed.

"It is simply service that measures success."By that measure, Carver’s success was extraordinary.

His life teaches that innovation and kindness go together. Even the humblest peanut can change the world.

Works Cited (MLA)

Carver, George Washington. How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption. Tuskegee Institute, 1916.

George Washington Carver National Monument. "George Washington Carver: Biography." National Park Service, www.nps.gov/gwca/learn/historyculture/biography.htm.

Holt, Marilyn Irvin. George Washington Carver: An American Biography. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Kremer, Gary R. George Washington Carver: In His Own Words. University of Missouri Press, 2017.

Library of Congress. "George Washington Carver Papers." www.loc.gov/collections/george-washington-carver-papers/about-this-collection/.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. "George

Washington Carver." nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/george-washington-carver.

Tuskegee University. "George Washington Carver." www.tuskegee.edu/about-us/legacy-of-tuskegee-university/george-washington-carver.